Social Networking as a Public Service

Understanding the Power of Local Citizens’ Networks

A Local Citizens’ Network is an online platform run as a public service for local residents. I shall divide this essay into two parts: (I) the Problem — a critique of privately run social networks detrimental to democracy, human rights and the rule of law; and (II) a Pilot Project — outlining a network run by the state, a democratic alternative for the benefit of local communities. A more transparent approach to online networking is feasible.

I. THE PROBLEM

All over the internet, networking space is privately owned. In recent years, online regulation of public behaviour has led to a parallel social contract imposed by companies with insufficient democratic input. This was an unforeseen and unavoidable development. In a constitutional democracy, however, the regulation of public behaviour is an exclusive prerogative of the legislator.

British citizens enjoy constitutional rights enshrined in a centuries-old struggle for participation, but users of most networks are faced with 17th-century standards: Companies have the same powers towards users as Charles I towards his subjects and even parliament. Shielded by a legal wall of protection, they can do anything as private companies and set their own rules. They offer a contract to which people agree voluntarily — or rather “voluntarily.” Joining a social network has become a matter of social, cultural and economic coercion. Those who refuse to join face disadvantages also in their professional career. Thus the argument that joining a social network is an entirely voluntary act is disingenuous.

For public interaction online, to which now most citizens are coerced by social life itself, British citizens must sign an agreement that disenfranchises them from civic liberties granted by acts of parliament. Private platforms reserve the right do as they wish with whatever account, “for any or no reason” (wording from Reddit). What

users sign up for is a contract with major implications for democracy, yet it is disguised as a commercial agreement. If your content is removed “for no reason”, you can take no legal action, because you have signed an agreement waiving your right to do so.

When you join a social network, in principle you agree to a commercial exchange of services, a “voluntary” agreement between private parties. But when, as a private company, and under the appearance of a commercial agreement, you set a body of rules to control the behaviour of millions, you perform an act akin to the promulgation of statutes. It may not be formal legislation, but materially it is. These laws are reinforced by what amounts to an autonomous body of jurisdiction comprising humans and algorithms often at odds with national jurisdictions.

Facebook, for example, has a body of so-called Community Standards which allows “newsworthy” content only in limited circumstances: “We do this only after weighing the public interest value against the risk of harm, and we look to international human rights standards to make these judgments.” This is an acknowledgement with major implications: Judgements are being made according to international statutes. We are dealing with an international court of human rights — self-appointed, with no institutional democratic legitimacy, passing its rulings unchallenged, affecting the lives of billions.

We have a national state whose citizens are also ruled by de facto online courts with a parallel body of jurisdiction. While our citizens enjoy the liberties of public life offline, in most online spaces they are bound to agreements that refuse to acknowledge the public character of their interactions — because that would mean subjection to the direct rule of national laws. And yet, what these private companies create and control is nothing but public space.

There are alternatives such as decentralised networks, now very much celebrated in the wake of a new Twitter-X crisis. Yet their rules are also written by private citizens, which becomes a democratic problem with increasing numbers of users.

A Local Citizens’ Network is under the direct rule of law. This is only possible if the network exists in a public space. But only the state, as a legitimate representation of the public, can create public space — a place where the law may rule without a private company, or private person, as an intermediary. Joseph Stiglitz agreed with me even before he knew it: The creation of public spaces for citizens online is a duty of the state, not a favour. It arises from the citizens’ right to life, liberty and security, which is also a human right (UDHR, Article 3). This security cannot be provided in spaces privately run. Nor should it be expected that private companies replace the rule of law. An internet with no public spaces is like a big city in which every street is privately owned.

II. A PILOT PROJECT

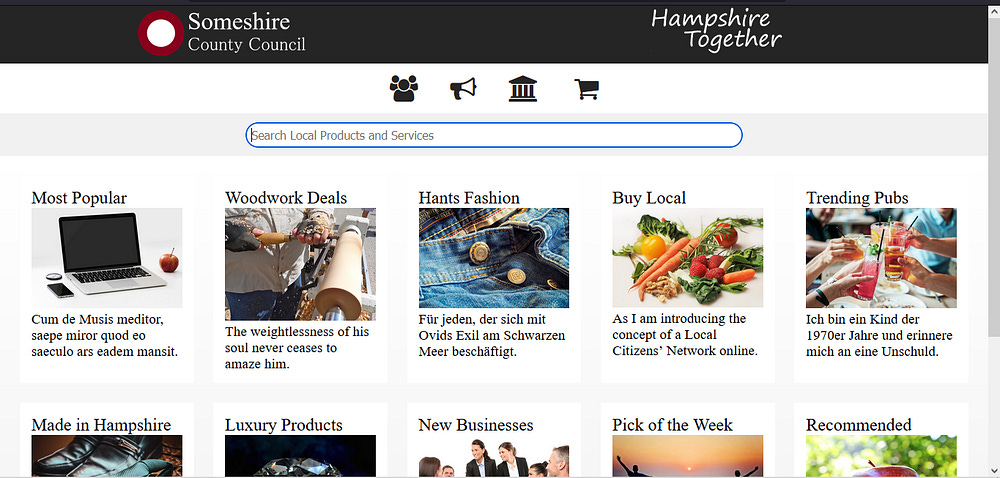

A space run by the state is truly public, ruled by democratically approved statutes. What I propose is the outline for a Local Citizens’ Network (LCN). Let’s look at a few elements of a potential pilot project.

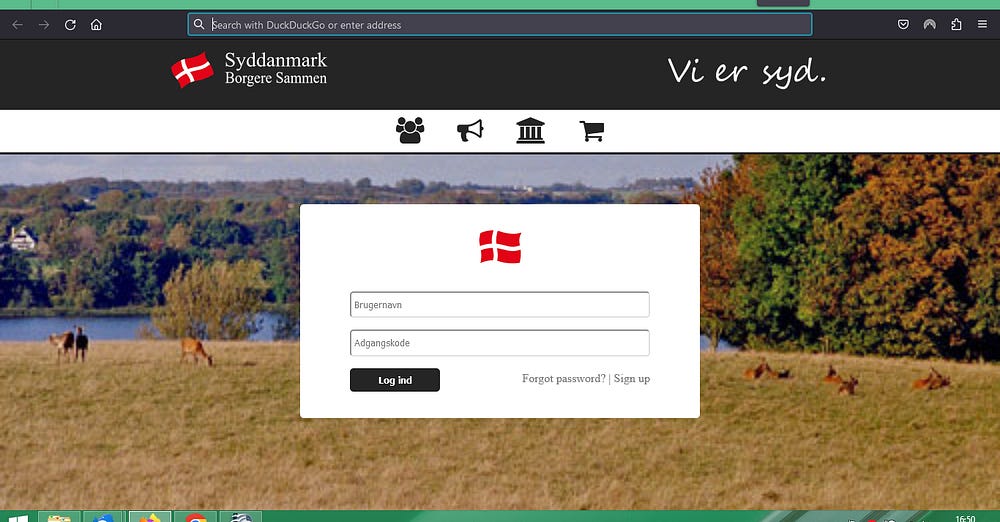

SIGNING UP: Only residents of a specific area may register for an account. Citizens sign up by submitting proof of residence to a registry office. Their name and address will be known to the office only. Once registered, they will be able to open a network account, with a handle of their choice.

Proof of residence helps to ensure that no one is above the law. Registered citizens have the assurance they are dealing with other real people at the law’s reach, rather than anonymous phantoms. While privacy must be afforded as prescribed by law, absolute anonymity would mean invisibility to the law.

To ensure public awareness, the local administration will notify every resident about the service, in writing. A number of residents will already be registered via local state websites, local libraries, national email services etc.

ACCOUNTS: Local residents may register for a Citizen’s Account, for private persons, a Group Account, for like-minded communities, or a Business Account, for registered companies. Small local businesses can use the latter to advertise products and services, as well as to socialise with local citizens and other businesses.

MARKETPLACE: The network features a marketplace available to small local businesses. Citizens may order, book or buy products and services directly within the network. The marketplace will also provide an interactive map and list with all registered businesses.

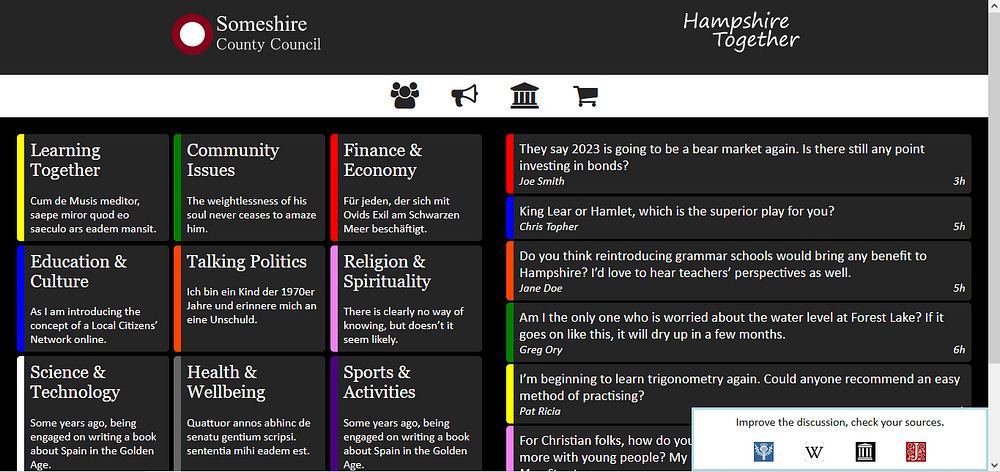

BOARD: The board is a space for citizens’ ads and announcements, a place for local job offers and seekers to find each other. Citizens can use the board to plan events and activities, organise meetings etc.

SQUARE: The square is a forum for debate and education, arts and culture, leisure and entertainment. Citizens can use it to discuss current affairs of politics and society, including local issues, listening to each other and contributing to a civilised democratic debate.

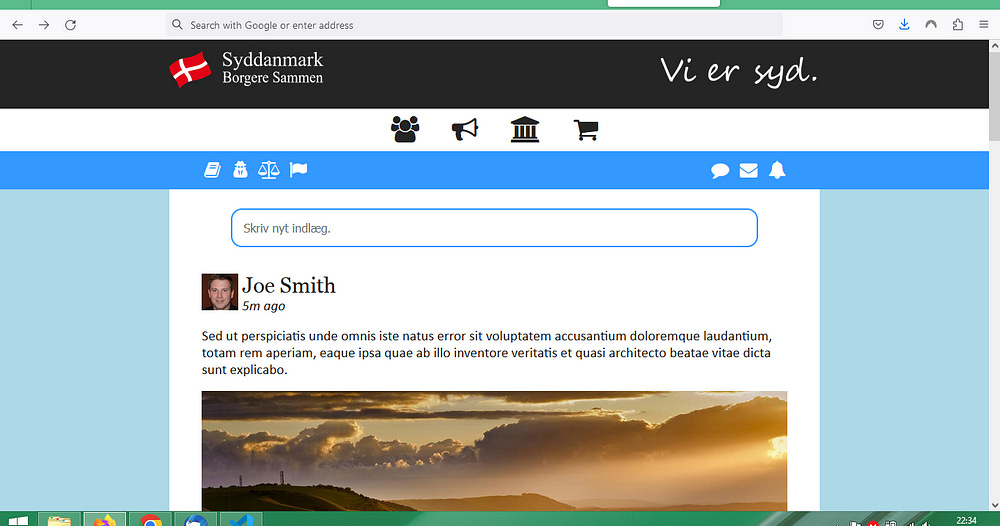

PROFILE: Every registered citizen has a personal profile on the network, on which he or she may upload content: text, document, image, audio, video, links. Citizens may only upload content they own or have a licence to. Any uploaded content belongs exclusively to the citizen.

SOCIALISING: Citizens will be able to form an unlimited group of friends. Their posts will be displayed on a timeline. There will be no quantification. The number of friends will not be publicly displayed. There will be no like button.

For any post, citizens may choose between (a) instant replies, (b) delayed replies, (c) no replies. In the second option, a citizen is allowed to reply only 24 or 48 hours after hitting the reply button. This is to avoid quick unreasonable reactions to a potentially controversial topic, encouraging slow thinking.

Citizens will be able to chat privately. The state must take all necessary steps to ensure that citizens’ data be protected against theft, including by hostile foreign agencies.

Privately owned social networks do not provide free socialisation. Only the state can provide this. Facebook, for example, makes it absolutely clear:

We don’t charge you to use Facebook or the other products and services (…). Instead, businesses, organisations and other persons pay us to show you ads for their products and services. Our products and services enable you to connect with your friends and communities and to receive personalised content and ads that we think may be relevant to you and your interests. You acknowledge that by using our Products, we will show you ads that we think may be relevant to you and your interests. We use your personal data to help determine which personalised ads to show you.

POLICING: The network will feature a police station with its own profile. Network citizens can be reported to community officers, appointed by the local police. Law enforcement will start with a conciliatory note to the offender, followed by a formal warning in case of recurrence. Should the reported offence continue after the formal warning, the police may take appropriate action.

A conciliation office, run in cooperation between the police and volunteer citizens, will provide conflict moderation. Citizens will be advised to seek the conciliation office before reporting a person to the police.

STATUTES: The network operates under the direct rule of law. Specific rules of will be drafted provisionally by the local administration. Every four years, the citizens will review the rules and make the changes they see fit, through a participatory procedure of debating and voting.

A local citizens’ network brings locals together in an organic and democratic way. This is its strength. It adds to the social and civic fabric of local communities by allowing members e.g. in the same isolated area to get to know one another. People want to connect with locals, but often do not know where to start. The network provides the space they need, with a credible potential of translating online interaction into real life. An LCN is a constructive contribution to isolated and marginalised groups, including the elderly and citizens in isolated rural areas. It empowers local businesses that have no chance in the privately owned giant networks. And it enhances trust in online networking by taking it to another ethical level. It remains to be seen how states and local administrations can be convinced of their duty to act.